“Things past redress are now with me past care” – William Shakespeare.

THE EMPLOYMENT relation between the manning agency representing the shipping company as the employer, and the seafarer as the employee, may cease not only upon the initiative or the employer based on authorized or just causes but also by reason of the free and deliberate act of the employee through resignation.

Evidently, the most important element in the act of resignation is the decision of the employee-seafarer to voluntary put an end to his employment arrangement with his employer without any pressure, force, or duress exerted upon him to arrive at such a resolution.

In the case of Intertrod Maritime, Inc. and Troodos Shipping Co., vs. NLRC and Ernesto dela Cruz (G.R. No. 81087, June 19, 1991), the Supreme Court so observed that “resignation is the voluntary act of an employee who finds himself in a situation where he believes that personal reasons cannot be sacrificed in favor of the exigency of the service, then he has no other choice but to disassociate himself from his employment.”

In the case of Great Southern Maritime Services Corporation, et. al. vs. Jennifer Anne B. Acuna, et. al. (G.R. No. 140189, February 28, 2005), the Supreme Court, citing Cheniver Deco Print Technics Corporation vs. NLRC (325 SCRA 758) and Pascua vs. NLRC (287 SCRA 554), added that resignation must be done with the intention of relinquishing an office, accompanied by the act of abandonment.

In a suit for illegal dismissal, an employer’s failure to show in clear terms the voluntariness of the employee-seafarer’s resignation would spell disaster to its cause. The case of Oriental Shipmanagement Co., Inc. vs. Hon Court of Appeals, et. al. (G.R. No. 153750, January 25, 2006) is explicitly clear on this point.

Here, the employer hired the respondents as Third Engineers to work on board its vessel for a one-year contract.

Not long after they began serving their respective contracts, the employer ordered them repatriated to Manila after they were made to sign so-called “letters of indemnity” which essentially provided the following: (a) the termination of their employment is based on the parties’ mutual agreement, (b) their employer will not institute any action against them as regards their service aboard their vessel while they on the other hand, have no claim of any kind against their employer, and (c) they have received all that is due them arising from their said employment.

When respondents sued their employer for illegal dismissal, the latter countered among others, that the respondents voluntarily resigned as evidenced by the letters of indemnity which carried their signatures. The Labor Arbiter and National Labor Relations Commission (NLRC) considered the resignation of the respondents to be valid.

The Supreme Court, agreeing with the Court of Appeals, ruled otherwise and held that the respondents did not resign but were illegally dismissed. The High Court found it illogical and strange for respondents to suddenly resign after barely beginning service of their 12-month contracts and then immediately file a complaint for illegal dismissal.

The well-entrenched rule is that resignation is inconsistent with the filing of a complaint for illegal dismissal. The Court was convinced that the respondents were forced to sign the letters of indemnity, inquisitively noting that since the documents contained a waiver by the employer to file disciplinary action against respondents, it only showed that respondents were in fact, given the impression that they would be disciplinarily dealt with if they did not sign the letters of indemnity.

For this reason, the letters of indemnity were deemed void or have no effect.

The acknowledgment by the respondents of their termination without any protest as shown in the letters of indemnity, is insufficient to satisfy the requirement that their resignation was done voluntarily.

Interestingly, the High Court regarded the letters of indemnity not as resignation letters but effectively as quitclaims that are viewed with strong disfavor.

Public policy dictates that they be presumed to have been executed at the behest of the employer and therefore, the latter is duty-bound to prove that the documents have been executed voluntarily by the employee.

In the afore-cited Great Southern Maritime Services Corporation case which was decided almost a year before the Oriental Shipmanagement Co., Inc. case, the Supreme Court likewise found the alleged resignation letters of the respondents-seafarers’ to be waivers or quitclaims which are not sufficient to show valid separation from work or bar them from assailing their termination.

Deeds a release or quitclaim cannot bar employees from demanding benefits to which they are legally entitled or from contesting the legality of their dismissal (Villar vs. NLRC, 331 SCRA 111). Accordingly, the employer cannot completely rely on said resignation letters to hinge its claim of voluntary resignation.

The High Court denied the theory of the employer that respondents voluntary resigned from employment as croupiers (card dealers) in a ferry casino, holding once more tha it is illogical for respondents to resign and then file a complaint for illegal dismissal.

The High Court denied the theory of the employer that respondents voluntary resigned from employment as croupiers (card dealers) in a ferry casino, holding once more that it is illogical for respondents to resign and then file a complaint for illegal dismissal.

The High Court, declaring that respondents were summarily dismissed without just cause, aptly explained:

“We find it highly unlikely that respondents would just quit even before the expiration of their contracts, after all the expenses and the trouble they went through in seeking greener pastures and financial upliftment, and the concomitant tribulations of being separated from their families, having invested so much time, effort, and money to secure their employment abroad.

Considering the hard economic times, it is incongruous for respondents to simply give up their work, return home and be jobless once again.”

The High Court also had the occasion to opine that the actions of some of the respondents in seeking and finding employment elsewhere while their illegal dismissal complaints were still under litigation cannot be used by the employer as reason to assert that resigned since they apparently had ready new jobs to go to.

It is crystal clear that for an employer to appropriately declare that an employee-seafarer resigned and was not terminated from employment, it must show by way of substantial evidence that the resignation was the employee-seafarer’s sole, unfettered, international, and conscious act. Wanting in this respect will most likely prove to be fatal to the employer.

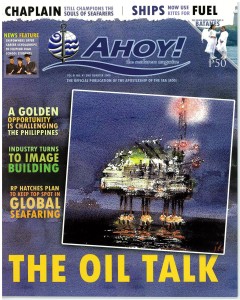

Source: Ahoy! the Seafares’ Magazine; Vol XI No. 47 – 2nd Quarter 2008, official publication of the Apostleship of the Sea (AOS).

Atty. Augusto R. Bundang, Partner of SVBB Law Offices. He can be contacted at: info@sapalovelez.com.